History

Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Lockheed Corporation President Courtlandt Gross, President John F. Kennedy, and Secretary of Labor Arthur Goldberg sign plans for progress in equal employment in the Oval Office, May 25, 1961.

**The Civil Rights Movement**

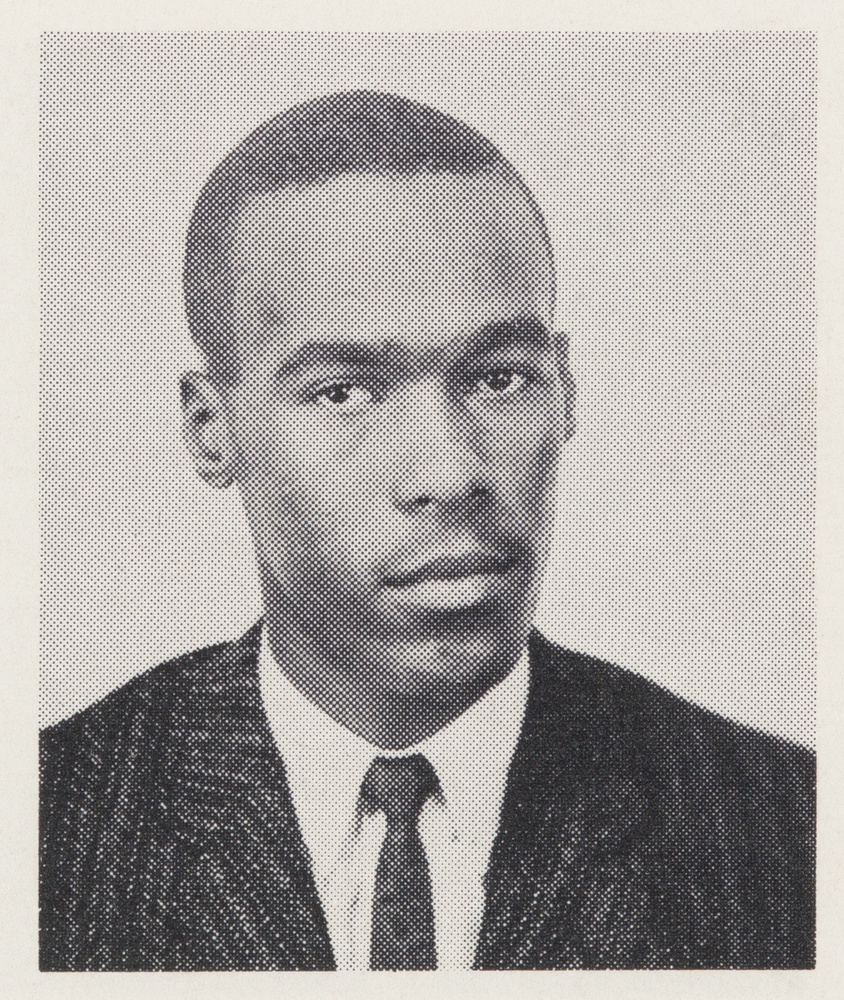

Kent Garrett ’63 co-author of “The Last Negroes at Harvard: The Class of 1963 and the 18 Young Men Who Changed Harvard Forever”

Harvard, Yale, and Princeton (the Big Three as Jerome Karabel dubs them in his book The Chosen) admitted students almost entirely on the basis of academic excellence for most of their histories. But this changed in the 1920s, when the traditional academic criteria failed to screen out students deemed “socially undesirable” (Karabel 2). A system of admissions focused solely on scholastic performance would inevitably lead to the admission of increasing numbers of Jewish students. This was unacceptable to the white men who presided over the Big Three. Their response was to invent an entirely new system of admissions.

The defining feature of the new system was the idea that admissions did not need to focus on academics alone. The top administrators of the Big Three recognized that relying solely on any single factor – especially one that could be measured – would deny them control over the composition of the freshman class. The presidents of the Big Three wanted the freedom to admit the boring sons of major donors and to exclude the brilliant children of immigrants, whose very presence prompted young white men – the probable leaders and donors of the future – to seek their education elsewhere.

Prior to the emergence of widespread institutionalized affirmative action was the Civil Rights Revolution. Brown v. Board of Education (1954) answered whether segregation of public education based on race violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The judges unanimously agreed that “separate but equal” which was established in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) was inherently unequal and a violation of the Equal Protection Clause. Yet, as the walls of Jim Crow segregation and inviduous exclusion collapsed, people began to realize that the mere prohibition of discrimination would fail to address the remnants of past oppression, such as education deficits caused by many decades of inferior schooling. Dissidents began to argue in favor of programs that would compensate for the losses caused by anti-black discrimination.

The men who ran Harvard, Yale, and Princeton were aware of these discussions and rumblings. But as of 1960, the struggle for civil rights had not led them to see why they should admit more black students. They believed they had done their part already! Their universities were committed to nondiscrimination and at least at Harvard and Yale, a modest number of African Americans had graduated over the years. So, what changed their mind?

**Yale**

President John F. Kennedy was elected in 1960. He campaigned as an advocate of civil rights and once in office, quickly signed Executive Order 10925 establishing the Presidential Commission on Equal Opportunity (the first time the phrase “affirmative action” was used in reference to race). The progress of the civil rights movement ebbed and flowed as it was met with severe backlash. In January 1961, two black students successfully integrated at the University of Georgia; four months later, Freedom Riders were beaten and arrested in Alabama (Karabel 380). Yale was among the first Ivy League colleges to respond to the charged atmosphere. In 1961-1962 Arthur Howe Jr., the Dean of Admission, hired Charles McCarthy to recruit qualified black students. Progress remained slow; in 1962, just six African American freshmen arrived in New Haven.

A Freedom Rider bus went up in flames in May 1961 when a firebomb was tossed through a window near Anniston, Ala. Passengers escaped without serious injury.

In the fall of 1962, President Kennedy summoned the leaders of five major universities, including Harvard and Yale, to the White House. According to Arthur Howe, the Yale Admissions Dean, who heard about the meeting from Yale President Kingman Brewster, Kennedy told the group, “I want you to make a difference… Until you do, who will?” Clearly, President Kennedy understood how influential the Ivy Leagues were and the broader ramifications their influence could make.

Brewster was deeply worried that America’s unresolved racial conflicts might tear the nation apart. For this reason, as well as his deep admiration for Martin Luther King Jr.’s commitment to racial justice and nonviolence, Brewster decided to award King an honorary doctorate in 1964 (Karabel 381). Brewster did not want to end up on the wrong side of history. The problem for institutions like Yale was that the supply of “qualified” blacks was extremely limited, given the prevailing definition of merit. Unless they altered their admission criteria, they would not be able to enroll substantial numbers of black students.

Kingman Brewster appointed Inky Clark as Yale’s new dean of admissions. Clark understood the need to update Yale’s admissions system and subsequently their prevailing definition of “merit.” The most important step was to admit that Yale’s seemingly neutral academic standards were, in the end, not neutral at all. For the first time, the Admissions Office acknowledged that a candidate’s academic profile was profoundly influenced by the opportunities that had been available to him. By 1965-1966, the Admissions Committee made it standard procedure to “seriously consider the possibility that SAT scores might reflect cultural deprivation rather than lack of intelligence.” Clark expanded recruiting, hired the first black counselor to the Admissions staff, increased its financial aid, and began working closely with organizations that targeted minorities (Karabel 384).

After the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., an unprecedented outbreak of riots shook the nation’s cities. Student revolutionaries at Columbia University staged their own uprising on April 23, 1968 (Karabel 389). The Black Student Alliance of Yale (BSAY) began to mobilize as well. 30 members of BSAY met with Dean Clark to demand Yale increase black enrollment of the incoming freshmen class to 12%. The BSAY mobilization pushed Yale’s black population to 8%, a bigger proportion than ever before. Yale sponsored BSAY recruiting trips and by 1969, Yale began sponsoring recruiting trips to recruit Asian Americans as well (Karabel 392).

A scene from the Columbia student protests.

**Princeton**

After 1967, the year of the riots, the African American admissions rate soared to 53%, almost double the rate of the previous year. A decade earlier it was alumni sons who were the main beneficiaries of “affirmative action” but by the late 1960s, special consideration was expanded to black students and other minorities. Princeton’s African-American proportion peaked at 10.4% in 1970. This was a result of appeals to secondary schools for more applicants, recruiting visits to areas with large minority populations, expanded contacts with community organizations, and efforts from the Princeton Association of Black Collegians (PABC) in recruiting students (Karabel 398).

**Harvard**

A Portrait of Richard Greener (Class of 1870), the first black graduate of Harvard.

Of all the Ivy Leagues in 1960, Harvard had the best reputation amongst the African American community. From 1939 to 1955, Harvard averaged about 6 black students a year, a considerably small portion of their class but the larges of proportion at any Ivy League college. In 1960, Harvard established an innovative program the looked for students (especially from the South) from economically and culturally impoversihed homes. The "Gamble Fund" was not specifically tagreting black student however they were major beneficiaries. This policy seems to be the predecessor for the Soicio-Economic Alternative (see below) which has provoked a lot of discussion recently. According to observers, affirmative action was already and instiutional policy at Harvard; the administration was willing to admit black students with inadequate test scores if there were indicators they could develop.

By 1963, black students at Harvard formed the Association of African and Afro-American Students (known simply as "Afro"). In 1965, Harvard had 42 black freshman, Yale had 23, and Princeton 12. After Martin Luther King Jr.'s assasination, tensions were high. The administration was confronted by Afro with a list demands. Among them was call to change Harvard's admissions policy toward blacks. Afro wanted Harvard to "admit a number of Black stufents proportionate to [the] percentage of the population as a whole" (Karabel 402). Four weeks after King's death, Harvard agreed to enroll a substantially higher number of black students. The agreement also called for better representation of blacks on the Admissions Office staff, direct involvement of undergarduates in recruiting African American students, and bringing more black candidates to visit Harvard. Under continued pressure from militant students, both black and white, admissions criteria was unofficially altered to giver preference to black students. The new dean of admissions, Chase Peterson, agrued that admitting such students would make campus more diverse and more intellectually stimulating. This statement shows that the Diversity Rationale (see below) existed long be for Bakke was decided in 1978.

Though Harvard did not establish official quotos, there seemed to be a target of admitting 100 black students. Harvard gave African-American candidates the same special (and far less controversial) treatment that has been afforded to group such as legacies and athletes for years. As with these other groups given special consideration, blacks had somewhat weaker academic credentials than the average freshman. However, unline legacies and donors, black admits came from families that were far less economically and culturally advantaged.

One African American faculty member criticized Harvard's admissions practices claiming that black freshman arrived with academic deficiencies. Martin Kilson cited statistics showing that only 48 percent of black students made the Dean's List while 82 percent of their white counterparts. By then, Harvard had already started to change their practices. Instead of admitting black students from disadvantaged backgrounds, they began recruiting black students that came from relatively privleged backgrounds that could transition smother.

**The New Admissions Formula**

By the 1970s, the Big Three had embraced a common ideal of diversity and adopted strikingly similar admissions policies. The new admissions process was need-blind, did not discriminate against women or Jews, and granted special consideration for historically underrepresented minorities as well as athletes and legacies. Admission was a highly subjective process that assessed personal as well as academic characteristics of the applicant. The Big Three gathered information not only on extracurricular accomplishments but also on highly subjective “intangibles.” Their demeanor, appearance, speech, social skills, affect, and personal presence were now under scrutiny by interviewers.

Supreme Court Cases

***Marco DeFunis Jr. v. Odegaard***

Marco Defunis, a graduate of the University of Washington, sued its law school in 1971, charging that it had rejected him in favor of less qualified minority students. In the summer of 1971, he filed a civil suit in Washington, claiming that he had been deprived of Equal Protection of the Law under the Fourteenth Amendment because the university had accepted members of favored racial groups despite their inferior academic records. The case was filed in the wake of intense backlash to colleges and universities' new admissions policies. "Affirmative action" was taking over national media and accusations of "reverse racism" filled the air.

The trial court upheld DeFunis’s claim and ordered the university to admit him. When the case wound up at the Washington Supreme Court, they ruled in favor of the University of Washington’s admissions practices. The court maintained that the university had a “compelling state interest” in producing “a racially balanced student body at the Law School” both for educational reasons and in order to rain minority lawyers in a multicultural society. The Washington Chief Justice dissented, “Racial bigotry… will never be ended by exalting the rights of one group or class over that of another,” clearly a preview of arguments to come (Karabel 487). The University of Washington made no efforts to expel DeFunis, but his lawyer said that they could legally dismiss him, so he decided to appeal.

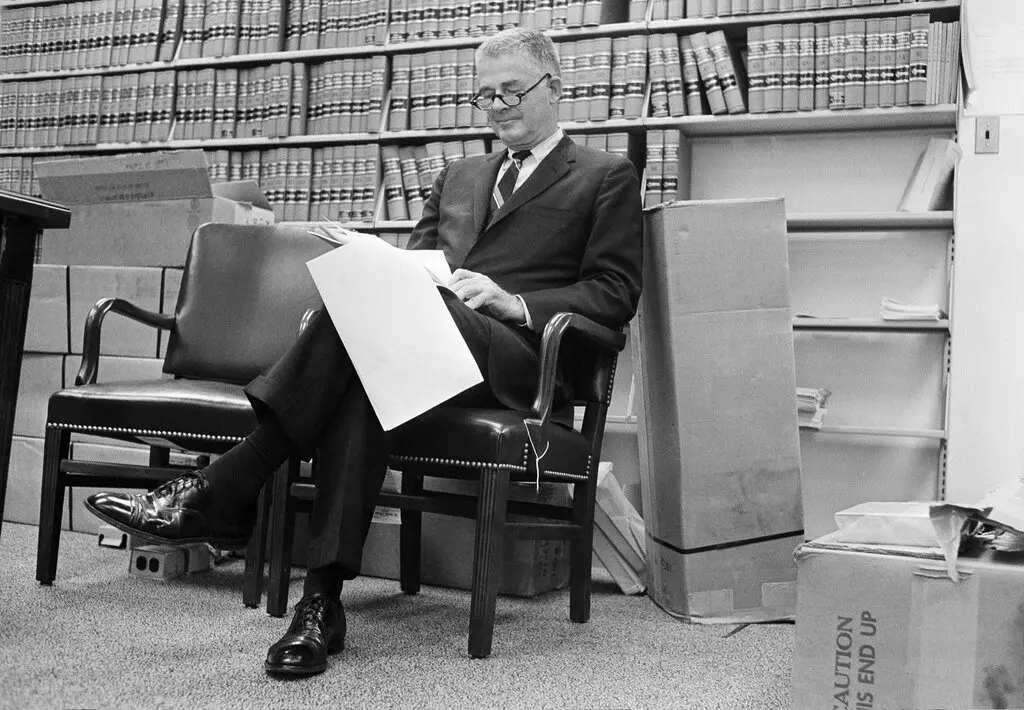

In November 1973, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. Harvard submitted an amicus brief written by Archibald Cox. He had already gained a reputation for integrity and fairness during Watergate and would play a significant role in the forthcoming Supreme Court case Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978). At the center of Cox’s argument was the state should not encroach on the autonomy traditionally granted to universities in deciding on admissions - an argument based in the university's first amendment right. Using the race of an applicant from a historically disadvantaged minority as a “tip factor” in admissions was necessary, the brief maintained, to produce the “diversity” that was indispensable to quality education. The Diversity Rationale was thus introduced to the Supreme Court for the first time.

Archibald Cox serving as the Watergate special prosecutor in 1973.

DeFunis was in his final semester of law school, and the University of Washington stated publicly that no matter the verdict, they would permit DeFunis to graduate. On April 23, 1974, the Supreme Court issued its decision: by a narrow majority, 5-4 (with Burger, Blackmun, Rehnquist, Stewart, and Powell in the majority), the justices declared the case moot, contending that since DeFunis would be graduating in any event, there was no issue before the Court that demanded resolution. The Court effectively kicked the can, saving its decision of affirmative action for another time.

One of the dissenting justices, William O. Douglas filed a full opinion on the merits of the case. The liberal justice stated DeFunis “had a constitutional right to have his application considered on its merits in a racially neutral matter” and “there is no constitutional right for any race to be preferred” (Karabel 489). On the other hand, he questioned the standardized tests that played such a large role in the admissions process at elite colleges. He denounced the Law School Aptitude Test (LSAT) as an example of mechanical criteria which are insensitive to the potential of minority students. As someone who is currently studying for the LSAT, I have to agree. Even today, the LSAT heavily benefits those with the financial means to afford a tutor or study program. A 2020 NYU Law Review Article stated the test is “a significant barrier to entry with disparate negative impacts on women, racial minorities, individuals of low socioeconomic status, and, perhaps most egregiously, those with disabilities.” In April 2022, the American Bar Association (ABA) proposed to eliminate the testing requirement. Opponents argue that the elimination of testing will force universities to rely on more subjective parameters which could also hurt minorities.

***Regents of the University of California v. Bakke***

In June 1974, a thirty-four-year-old white man of Norwegian ancestry filed suit against the University of California at Davis Medical School, claiming that it had rejected him in favor of less qualified minority students. Specifically, Davis had set aside sixteen out of one hundred seats for qualified "disadvantaged" "blacks,""Asians," "Indians," or "Chicanos" (Kennedy 182). Allen Bakke’s qualifications failed to gain him admission to any of the twelve medical schools to which he applied. He made it to the interview stage at UC Davis but was ultimately rejected. His essential claim was that UC Davis’s policy of reserving 16 percent of the entering class for minorities “who are judged apart from and permitted to meet lower standards of admission” than white applicants denied him equal protection of the law (Karabel 490). It was confirmed that the average GPA of "special" admittees was 2.62 and Bakke himself had a GPA of 3.44. He received a 97 on his MCAT while the average for the disadvantaged group was 37.

The lower courts ruled in Bakke’s favor but did not order UC Davis to admit him since it was unclear if he would be admitted in the absence of the medical school’s special program for minorities. The California Supreme Court issued a sweeping 6-1 ruling in favor of Bakke. On the crucial issue of whether Davis’s program was constitutional, the court’s opinion was an unequivocal no. “The program, as administered by the University, violates the constitutional rights of nonminority applicants because it affords preference on the basis of race to persons who, by the University’s own standards, are not as qualified as nonminority applicants denied admission,” stated the court. They ordered University of California to admit Bakke to the Medical School at UC Davis.

The University of California appealed to the Supreme Court. The University of California chose the one and only Archibald Cox to present its case. The case received an immense amount of publicity. Cox stated, “There is no racially blind method of selection which will enroll today more than a trickle of minority students.” Archibald Cox had come to the same conclusion that the Big Three had just a decade ago - neutral academic standards were, in the end, not neutral at all. Moreover, allowing universities the autonomy to try and solve this problem gives all of us the benefit of trial and error.

The tried and true argument based on compensatory justice worked on the Court’s liberals. However, Archibald Cox needed to appeal to the Court’s conservatives who disfavored this argument. Justice Lewis Powell, in fact, had railed against “the guilt-ridden views of those who talk about reparations for past injustice” in a speech in 1970. Instead, Cox emphasized that the court’s past interpretation of the Constitution provided a school the freedom to pursue the educational benefits of diversity, including racial diversity, “to prepare students to live in a pluralistic society.” This was not the first time the Diversity Rationale had been offered to the Supreme Court, but this would be the first time the Supreme Court ruled on the merits of the justification.

Outside the Supreme Court on Oct. 12, 1977, before the oral argument in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke.

After more than eight months of deliberations, the Court announced its decision on June 28, 1978. Four of the justices - Stevens, Burger, Stewart, and Rehnquist - believed the University’s special admissions program violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by excluding Bakke from the Medical School because of his race. The Court’s four more liberal justices - Brennan, Marshall, Blackmun, and White - argued that “we cannot… let color blindness become a myopia which masks the reality that many ‘created equal’ have been treated within our lifetimes as inferior both by the law and their fellow citizens,” and concluded that “government may take race into account when it acts not to demean or insult any racial group, but to remedy disadvantages cast on minorities by past racial prejudice” (Karabel 496). The deciding vote was in the hand of Justice Lewis Powell. Joining the conservative justices in ordering Bakke admitted and in rejecting the claims of compensatory justice, he aligned himself with the liberals on the crucial issue: whether race could be a factor in college admissions. Powell ruled that universities could consider race when doing so was necessary to obtain “the educational benefits that flow from an ethnically diverse student body.” Powell provided Harvard as an example of a program that passed legal muster. His view prohibited quotas, created a unified process for minority and nonminority applicants, and used criteria flexible enough to consider race as just one factor among others, including geography or life spent on a farm.

The rationale allowed affirmative action to endure but left it vulnerable, stripping away history and the moral underpinning to remedy racism. The diversity defense is in many ways profoundly conservative, for it preserves the status quo in higher education. Moreover, Powell had sharply rejected one of the central arguments of race-attentive admissions: race may be taken into account “to remedy disadvantages cast on minorities by past racial prejudices.” Powell's decision eroded the moral foundations on which affirmative action had been built (Karabel 499). Ever since Bakke, the defenders of race-based preferences have had to fight to preserve it, in effect, with one hand tied behind their backs.

***Grutter v. Bollinger*** and ***Gratz v. Bollinger***

Jennifer Gratz and Patrick Hamacher applied to the University of Michigan's College of Literature, Science, and the Arts (LSA), were rejectedm and sued in 1997. Barabara Grutter applied to the University of Michigan Law school, was rejected and also sued in 1997. Both plaintiffs claimed that they were victims of unconstitutional reverse racism. The Supreme Court heard arguments in April 1, 2003, and issued decisions on June 23, 2003. A majority of justices embraced the proposition that diversity is a compelling justification for racial selectivity. The Court affirmed that the admissions policies should be "narrowly tailored" which led to a victory for the law school in Grutter and a defeat for LSA in Gratz.

In Grutter, the conservative needed to win a majority this time was Sandra Day O'Connor. She argued that diversity was a compelling state interest that promoted cross-racial understandings, breaks down racial stereotypes, and enables students to better undestand people of other races (Kennedy 212). Moreover, diversity enriches everyone's edication by providing livelier discussion and had been narrowly tailored in Grutter. O'Connor even pushed farther advocating for affirmative action programs beyond higher education, "high-ranking retired officers and civilian leaders of the United States military assert that, based on their decades of experience, a highly qualified racially diverse officer corps... is essential to the military's ability to fulfill its principal mission to provide national security." Justice O'Connor did surprise some at the end of her opinion by proposing a sunset provision: "We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary." Ultimately, the Court ruled that it would be best to leave such “complex educational judgments” involved in admissions decisions to the “expertise of the university.” This allowed admissions officers at elite universities to possess both the discretion and the opacity to pursue institutional interests as they saw fit.

Gratz operated under a different selection scheme. The college sought diveersity under the guidelines set forth by Powell in Bakke. However, unlinke the law school, which subjected all students to the same application process, LSA automatically awarded any minority applicant 20 points, basically one-fifth of the points needed to gain admissions. Reinquist wrote for the majority complaining that the automatic bump was in conflict with Powell's requirement of flexible, individualized assessment. The Court, with Sandra Day O'Connor amongst the majority this time, ruled in favor of Gratz.

The Court held that race could serve as a "plus" for purposes of diversity but that any process using race would be narrowly tailored. One of the main critiques that blossomed out of the Grutter and Gratz decisions was that the Court had redefined the meaning of Strict Scrutiny. Strict scrutiny was supposed to be used when the government does something that prompts judicial anxiety, upending the presumption of legitimacy normally enjoyed by the government and replacing it with distrust. Now, as Justice Ginsburg wrote in her dissent, the Court was applying "strict scrutiny" to all race dependent decisions - even those that used benevolent discrimination like affirmative action. Grouping race-based policies like affirmative action and Jim Crow laws has created the impresssion amongst the public the discrimination is inherently negative. In Ginsburg's view, "government decisionmakers may properly distinguish between policies of exclusion and inclusion" (Kennedy 215).

***Fisher v. University of Texas (Two Cases) ***

On February 21, 2012, the Supreme Court announced that it would review Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin. The plaintiffs Abigail Fisher and Rachel Michalewicz, white applicants who were rejected by University of Texas (UT) in 2008. In 1996, in Hopwood v. Texas, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals rule that UT would no longer be permittted to use race as a plus for diversity purposes. Subsequently, the number of black and Latinx students plummeted. In response, legislation was passed that authorized Texas high school seniors in the top 10 percent of their class would gain automatic acceptance to any Texas state university. Since schools are often racially distinct enclaves, the Top Ten Percent Plan would allow the best racial-minority students to be automatically admitted. Whites could benefit from this plan as well, but overall it benefitted minorities disproportionately.

The question presented was whether the Supreme Court's decision interpreting the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteeenth Amendment permitted UT's use of race in undergraduate admissions decisionos. Fisher claimed that either this use of race did not fall into the guidelines outlined in Grutter or that Grutter must be overturned.

Justice Anthony Kenendy delievered the opinion for the 7-1 majority (Kagan recused herself because she served as solicitor general when the case was before the court of appeals). The Supreme Court vacated the 5th Circuit Court's opinion and remanded the case back to the 5th Circuit so they would review it under the "strict scrutiny" standard this time. However, this was just the first part of the Fisher saga which is why sometimes you will see Fisher I and Fisher II. After being remanded, the appellate court reaffirmed the lower court's decision by holding that UT's use of race as a consideration was narrowly tailored to the legitimate interest of promoting education diversity and thereford satisified strict scrutiny. Once again, Kennedy delivered the opinion. The Court's 4-3 majority held that UT's use of race was narroly tailored to serve a compelling state interest. This decision reaffirmed the Grutter precedent.

The Diversity Rationale

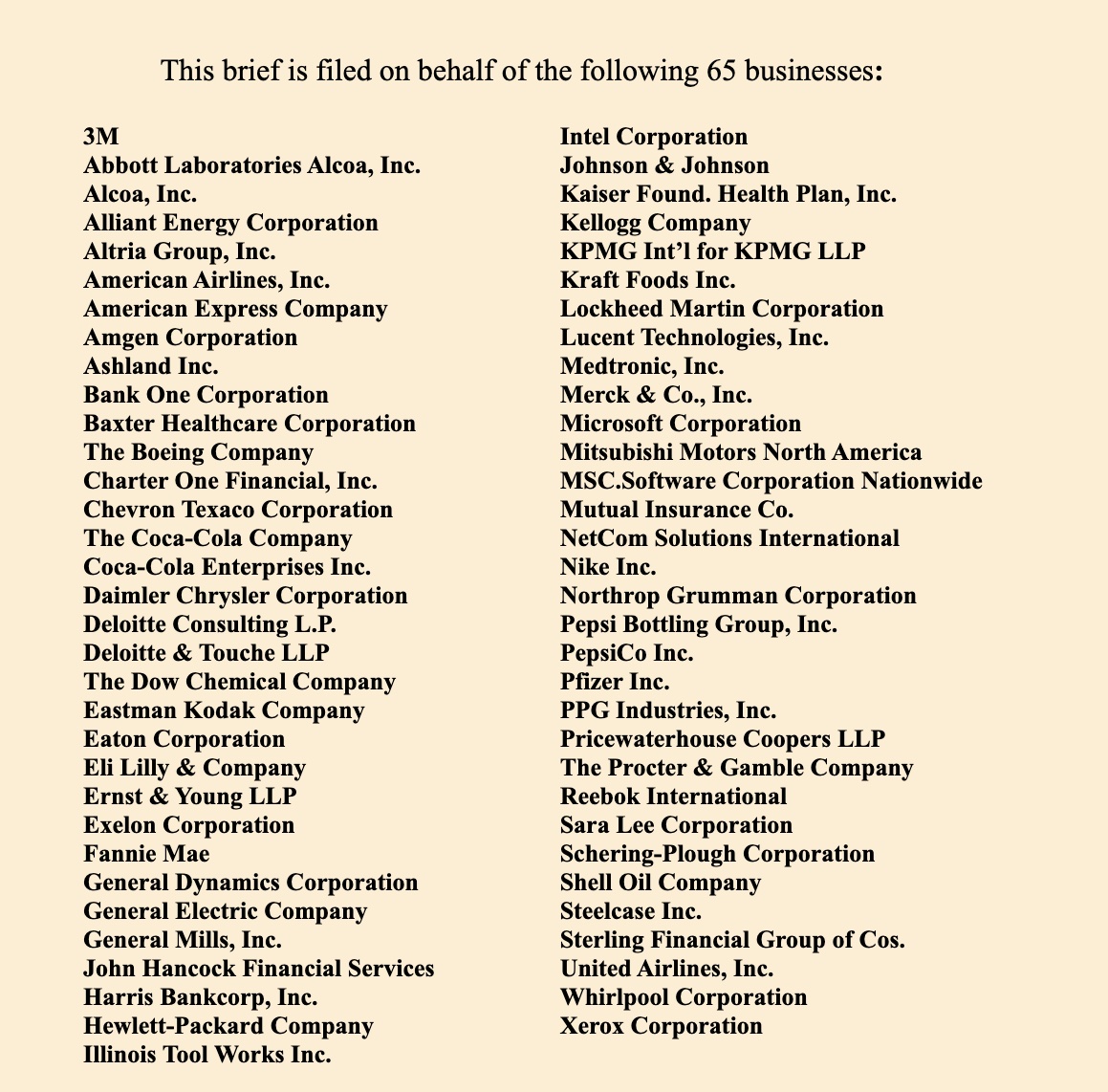

The briefs that appeared to save affirmative action in 2003 came from top military leaders

and executives at companies like Coca-Cola and Texaco.

When a Supreme Court case involves race, national origin, religion, or alienage, the Court applies the most stringent form of judicial review called “Strict Scrutiny.” In Bakke, Justice Powell maintained that "racial and ethnic distinctions of any sort are inherently suspect and thus call for the most exacting judicial examination." He insited that any and all racial distinctions should trigger the same searching judicial inquiry - "stict scrutinby." Pursuant to strict scruitiny, judges are skeptical of the governmental conduct in question and presume it to be illegitmate. Under the strict scrutiny test, laws must be narrowly tailored to reach a compelling state interest for the Court to affirm their validity. In Bakke, the diversity rationale was established as the state’s compelling state interest for affirmative action. Before researching the diversity rationale, I thought the justification was merely concocted to satisfy constitutional review by the Supreme Court. In fact, many liberals and conservatives alike do not believe in the diversity rationale. Multiple justices have already shown their distaste for this rationale. Clarence Thomas stated during oral arguments in 2022, “I've heard the word diversity quite a few times and I don't have a clue what it means. It seems to mean everything for everyone.” However, after researching the diversity rationale, I found there were real, measurable benefits that resulted from the implementation of affirmative action policies.

Affirmative action can facilitate, through racial diversity, enriched learning and wiser decision-making. In Grutter, 65 leading businesses submitted an amicus brief stating that “the existence of racial and ethnic diversity in institutions of higher education is vital to amici’s efforts to hire and maintain a diverse workforce… is important to amici’s continued success in the global marketplace.” Close observers of various types of organizations – universities, firms, juries, etc. – maintain that diversity enhances their overall performance. Not to mention, as Sandra Day O'Connor did in her opinion in Grutter, the military considers diversity necessary for national security purposes. The diversity rationale is a relative newcomer among justifications for affirmative action. It did not attain prominence until Bakke decision and has been viewed with skepticism ever since, even among strong proponents of affirmative action.

The “diversity defense” is a profoundly conservative argument, for it preserves the status quo in higher education. By consciously rejecting arguments that claim the very criteria used to measure merit perpetuate racial and class privilege, the diversity defense obscures some of the main reasons that leading universities adopted affirmative action in the first place: to right the wrongs of the past and to integrate the elite of the future.

Compensatory Justice

The reparations theory of affirmative action is known by various labels, including rectification, restitution, remediation, correction, and compensation. Key to this theory is the idea that leaving past wrongs unadressed cause them to become refreshed wrongs.

Racial affirmative action partially redresses debilitating social wrongs that have been ongoing since at least the Civil War. Racial minorities, and black in particular, have suffered from racist mistreatment at the hands of the federal government, state governments, local governments, and private parties. This oppression has produced a cycle of self-perpetuating problems that will not resolve themselves without interventions that go beyond prohibition of intentional racial mistreatment. Past wrongs have diminished the educational, financial, and other resources that marginalized groups can call upon, and have thus disadvantaged them in competition with whites. As President Lyndon B. Johnson said, “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, ‘You are free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair.” It is not enough to simply end discrimination on the basis of race. Reasonable efforts to rectify the negative legacy original past wrongs are also morally required. “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, ‘You are free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair.”

One problem with this argument is that affirmative action based on grounds of compensatory justice always entails an assumption or a finding of culpability for some past or present wrong. Common claims of “reverse discrimination” in the name of white inocence and protests against the supposed intrusiveness of “big government" arise. It is a familiar trick, the kind of rhetorical sleight of hand that had become a staple of conservative pundits everywhere, whatever the issue: taking language once used by the disadvantaged to highlight a societal ill and turn it on its ear. The problem isn’t sexual harassment in the workplace; it’s humorless “feminazis beating men over the head with their political correctness.

Even some on the anti-racist Left also objected to especially favoring blacks. Bayard Rustin, an African American leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, and nonviolence, saw it as a misdiagnosis that wrongly elevated racial conflict over the centrality of class conflict and a misprescription that would further weaken the prospects for progressive working-class unity by exacerbating racial resentments.

Socio Economic Alternative

Like all policies, affirmative action entails costs. It risks instilling excessive race-mindedness, stoking resentments, and diverting attention from those whose needs are even greater than those typically benefited by positive discrimination. Richard Khalenburg has become the poster-child for a socio-economic alternative.

- Get rid of preferences for ALDCs (Athletes, Legacies, Donors, and Children of Staff)

- Increase community college transfers

- Give a break to students who have excelled in struggling schools, neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, families with low net-worth.

- Pump up the financial aid

- Look for applicants in towns that do not normally send students to highly selective schools

If it sounds expensive, that's because it is! Colleges and universities that admit more low-income students would have to support them through stipends and scholarships, and there is an added cost to recrutuit them as well.

One positive for this proposal is that it seems to be popular. Anemona Hartocollis was surprised after writing about Khalenburg, "A lot of people are intrigued by what he is proposing and support it."

The First Amendment Argument

Time and time again, the Supreme Court has upheld colleges and universities the autonomy to create their own admissions policies. If affirmative action is struck down by the court, there could be a first amendment argument to be made. Justice Lewis Powell’s opinion in Bakke even recognized “a constitutional element, grounded in the First Amendment, of educational autonomy.”

Constitutionality

There is nothing in the Constitution’s text, in the intentions of its framers, or in the logic of its mission that should be seen as precluding racial affirmative action. The Supreme Court has condemned affirmative action because it runs afoul of what it claims is a mandate of constitutional color blindness. The court is wrong. The Constitution does not compel color blindness and should not be seen as harboring an aspiration for color blindness.

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment sates, "No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." The thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth amendments are commonly known as the Civil War Amendments because they were created to outlaw slavery. This creates a problem for justices who subscribe to originalism because clearly the author did have race at the time. The authors of these admendments wished to incorporate blacks into society. Affirmative action policies wish to continue supporting integration of racial minorities by admitting them into higher education.

Ramifications

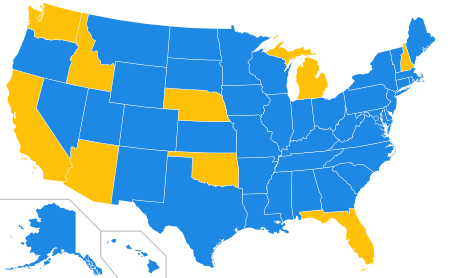

State bans affirmative action and other forms of selective employment

As we await SFFA v. UNC and SFFA v. Harvard decisions, we look to the states as labortories of Democracy to understand what striking down affirmative action would actually look like. Many are unaware of the fact that nine states have already banned affirmative action. In 1996, California voters approved the nation's first ballot initiative banning consideration of race and gender public educatioon, hiring, and contracting known as Proposition 209.

California and Michigan ended affirmative action years ago. Since then, top colleges and universities in both states have tried a range of race neutral stragies to recruit Black, Hispanic, Native American, and other minority students. The results have been sobering. At UCLA, UC Berkeley, and the University of Michigan, enrollment of underrepresented students of color sharply declined after the bans, and the number still lags. Once again, we can see how race-neutral policies are not race neutral at all - they hurt people of color. There are measures that colleges, but administrators and experts have found that there is no subsitute for privileging race as an admissions criterion. Some actions such as ending SAT requirements, providing scholarships to low-income students, and reaching out to high schools with low-income or minority students have only marginally boosted diversity.

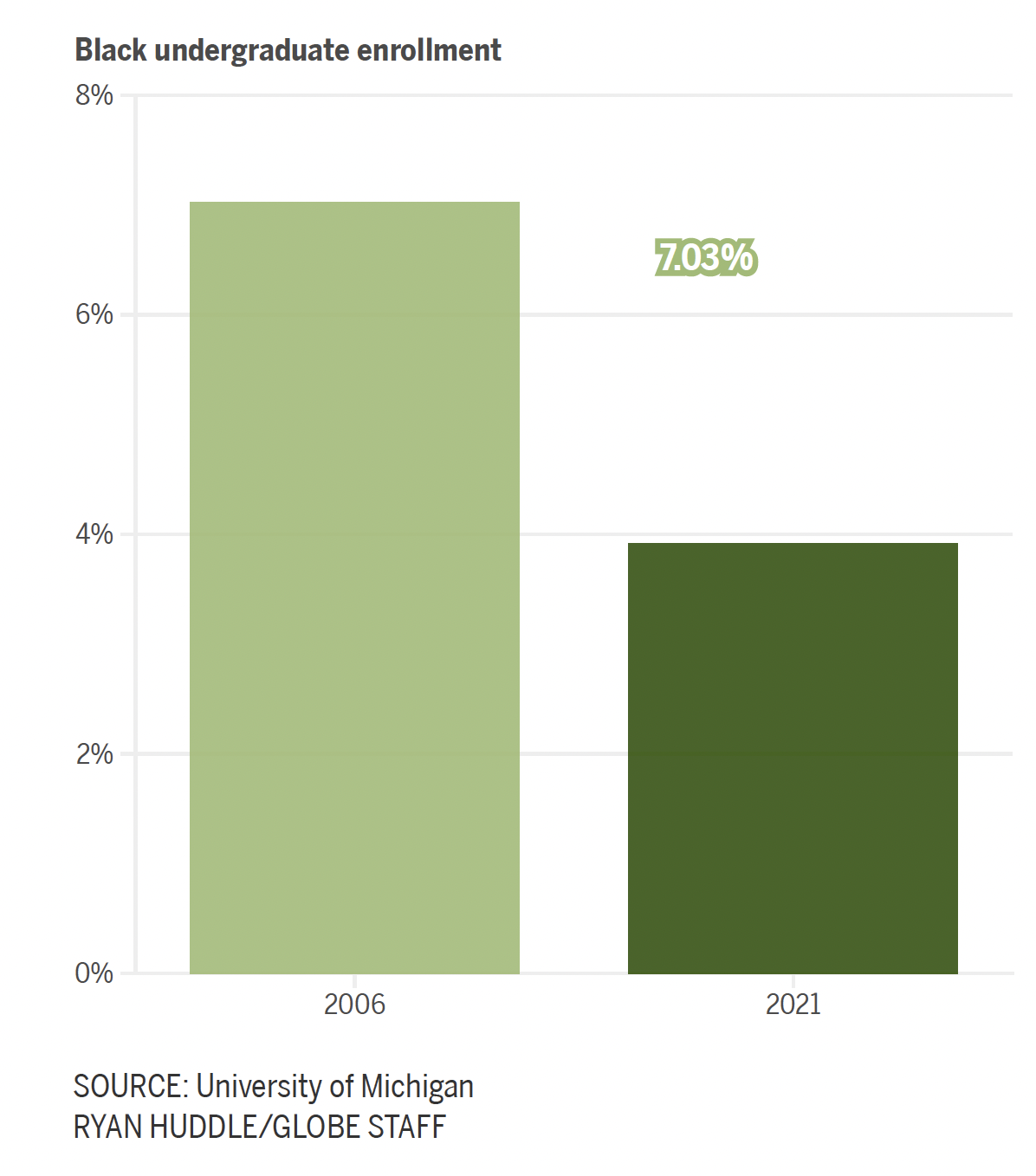

At Berkeley, the number of Black and Latino student in the firt-year class was cut in half immediate after the ban. UCLA saw simiiliar results. At the University of Michigan, enrollment of Black students has fallen 44 percent and the number of Native American students has dropped 90 percent since the ban was passed in 2006.

The afrtermath of affirmative action ban for University of Michigan

The ramifications do not end here. In California, about 15 years after Propositioon 209, there were about 1,000 fewer high-earning Black and Hispanic professional in the state, said Yale researcher Zachary Bleemer (Burns 2023).

Polling

When Gallup asked Americans "Do you generally favor or oppose affirmative action programs for racial minorities?" Without a definition or explanation, 61% were in favor and 30% were opposed as of 2018. This is an increase from 47-50% in the early 2000s. However, when Pew asked in 2019, "When it comes to decisions about hiring and promotions, do you think companies and organizations should take a person's race and ethnicity into account, in addition to their qualifications, in order to increase diversity in the workplace (or) should only take a person's qualifications into account, even if it results in less diversity in the workplace?" 74% chose the latter. NORC General Social Survey asked a similar question in 2018 and found The results show that 72% of U.S. adults oppose giving preference to Black Americans in hiring and promotion, including 43% who say they oppose strongly.

This evidence shows that Americans clearly favor the idea of remedying past injustice towards African Americans and reducing inequalities of outcomes. But when it comes to policies that explicitly take race into account in making hiring and promotion decisions in order to remedy past discrimination and overcome implicit bias, the public demurs.

What do you think? Vote in the poll below and vote in your local, state, and elections!

References

Amar, Vikram David, and Evan H. Caminker. Constitutional Sunsetting? University of Michigan, https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2932&context=articles.

“Bakke v. Regents of University of California.” Justia Law, https://law.justia.com/cases/california/supreme-court/3d/18/34.html.

Bazelon, Emily. “Why Is Affirmative Action in Peril? One Man's Decision.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 15 Feb. 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/15/magazine/affirmative-action-supreme-court.html.

“Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1).” Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/347us483.

Brown, Melissa. “Freedom Riders Traveled Deep into the South in 1961. Klansmen Beat Them, Then Set Their Bus on Fire.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, 31 May 2022, https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/nation/2021/10/04/freedom-riders-nearly-died-alabama-kkk-fought-progress/5611652001/.

Columbia Law Review. “Assessing Affirmative Action's Diversity Rationale.” Columbia Law Review, 30 Mar. 2022, https://www.columbialawreview.org/content/assessing-affirmative-actions-diversity-rationale/.

Crawford, Curtis. “Gratz v. Bollinger and Grutter v. Bollinger THE BRIEFS.” Debating Racial Preference, http://www.debatingracialpreference.org/GRATZ-GRUTTER-Amici-Businesses.htm.

Gibson, Katie. “Painting Unveiled of College's First African-American Graduate.” Harvard Gazette, Harvard Gazette, 15 Mar. 2019, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2016/04/painting-of-colleges-first-african-american-graduate-unveiled-in-annenberg-hall/.

Hartocollis, Anemona. “The Liberal Maverick Fighting Race-Based Affirmative Action.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 29 Mar. 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/29/us/richard-kahlenberg-affirmative-action.html.

Karabel, Jerome. The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton / Jerome Karabel. Houghton Mifflin, 2006.

Kennedy, Randall. For Discrimination: Race, Affirmative Action, and the Law. Vintage Books, a Division of Penguin Random House LLC, 2015.

Knox, Liam. “Aba Proposes Eliminating Standardized Tests for Law School.” Inside Higher Ed | Higher Education News, Events and Jobs, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2022/06/15/aba-proposes-eliminating-standardized-tests-law-school.

Lewis, Anthony. “The Bakke Argument.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 13 Oct. 1977, https://www.nytimes.com/1977/10/13/archives/the-bakke-argument.html.

Mak, Aaron. “Harvard Isn't off the Hook.” Slate Magazine, Slate, 3 Oct. 2019, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2019/10/harvard-affirmative-action-case-legacies-athletes-aldc.html.

Milov-Cordoba, Michael. “Beyond ‘Valid and Reliable’: The LSAT, ABA Standard 503, and the Future of Law School Admissions.” NYU Law Review, 22 Dec. 2020, https://www.nyulawreview.org/issues/volume-95-number-6/beyond-valid-and-reliable-the-lsat-aba-standard-503-and-the-future-of-law-school-admissions/.

“Plessy v. Ferguson.” Oyez, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1850-1900/163us537. “Statement by the President upon the Signing of a Joint Statement by Lockheed Aircraft Corporation and the President's Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity.” The American Presidency Project, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/statement-the-president-upon-the-signing-joint-statement-lockheed-aircraft-corporation-and.

“Top 10 Percent Law.” UT News, 23 Sept. 2021, https://news.utexas.edu/topics-in-the-news/top-10-percent-law/.

Vanity Fair. “Inside the 1968 Student Protests That Changed the World.” Vanity Fair, Vanity Fair, 26 Mar. 2018, https://www.vanityfair.com/news/photos/2018/03/inside-the-1968-student-protests-that-changed-the-world.

Wheeler, Sharae. “DeFunis v. Odegaard.” The Seattle Civil Rights and Labor Project, University of Washington, https://depts.washington.edu/civilr/DeFunis.htm.

“‘The Attack on American Institutions’ by Lewis F. Powell, Jr..” Scholarly Commons, Washington and Lee University of Law, https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/powellspeeches/8/.